East Austin Yellow Jackets Tailored by Joyce

Jazz great Kenny Dorham and Motown's Gil Askey came out of the L.C. Anderson High School Band

Long before Roky and Janis, Austin’s reputation as a music town was forged by the L.C. Anderson High School band. Resplendent in uniforms as bright as a September sunrise, the Yellow Jacket Band would trek to the annual Prairie View Interscholastic League marching band competitions and usually come back with a trophy. Under B.L. Joyce’s directorship, the Jackets of Anderson won the state championship seven times from 1940-1953.

“If we got second place it was a big disappointment,” said Ernie Mae Miller, a tenor sax player with the band from 1940-43, who went on to a lengthy career as a singer/pianist. “We just sounded better than the other bands. When they called our name as the winner, we were like, ‘Of course!’” The jazz trumpet immortal Kenny Dorham was a Yellow Jacket (Class of ‘41), as was Gil Askey, the future Diana Ross musical director, and trumpeter Martin Banks of Harlem’s Apollo Theater house band. Though Charlie Parker’s bassist Gene Ramey went to Anderson, he graduated before Joyce started the band in 1933.

Joyce was forced to resign in 1953 when a new statewide rule required high school band leaders to have music degrees. His replacement was protege Alvin Patterson, who held the job until school desegregation forced Anderson to close in 1971. In the ‘60s, Patterson also led the Rhythm Kings, a jazz/soul group consisting of Black high school band directors, who played weekends at the Jade Room on San Jacinto.

For most of the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, the East Side was almost invisible to the rest of Austin. The predominantly black neighborhood on the other side of the freeway might as well have been in another county. But when the Yellow Jacket Band marched down Congress Avenue to the State Capitol in 1959 for Gov. John Connally’s inauguration, East Austin’s presence was full and pronounced. Wow! The band looked and sounded like it had something to prove. Other marching bands would almost rather follow horse manure.

A master tailor who worked out of his house at 1706 E. 14th St. and taught the trade at Samuel Huston College, Benjamin Leo Joyce was also a musician who played tuba in the Army band during World War I. With a desire to give Black students the same kind of musical training available in the white schools, Joyce started canvassing East Austin in late 1932 looking for kids who wanted to play. He also solicited neglected instruments.

Joyce made the uniforms that first year- no beginning band ever looked so snappy- and the players were expected to carry themselves in a manner consistent with their sartorial splendor. “Mr. Joyce didn’t put up with an ounce of foolishness,” said Ernie Mae, whose grandfather Laurine Cecil Anderson was the school’s namesake. “You couldn’t play no jazz either.”

Joyce bent his strict “no jazz” rule only one time that Alvin Patterson could remember. “We were playing football against our rival, Wheatley in San Antonio, and they were beatin’ us,” he recalled. “But even worse, their band was showing us up, playing all these hot big band swing numbers. So Mr. Joyce called me over and said, ‘What was that swing thing you guys were playing the other day when you thought I was out of listening range?’ I said that was ‘Tuxedo Junction’ and he said, ‘OK, let’s hear it.’” As Dorham played the Erskine Hawkins part perfectly, even Joyce had a smile on his face. The Anderson football team also rallied to win the game.

Motown’s glue, Gil Askey

Gilbert Askey may have been the second-greatest trumpet player to come out of the Yellow Jackets Band, but he was the only one to garner an Oscar nomination- for his Lady Sings the Blues score in ‘73.

“I left Austin for good at age 17 in 1942,” Askey said during his annual visit home in 2010. “But Austin has never left me.” He never forgot his first bandleader B.L. Joyce, who came from an era when educators were bigger heroes in East Austin than footballers or singers.

Over coffee at Denny’s, Askey put off questions about his glitzy musical résumé and instead told long stories of growing up dirt poor in East Austin. He made imaginary street maps with the side of his hand — “Hackberry, Juniper, Willow…” he’d recite.

Askey helped discover the Jackson 5 and was musical director on tours by the Four Tops, the Temptations, Gladys Knight and the Supremes. He wrote with Curtis Mayfield and penned Linda Clifford’s disco hit “Runaway Love,” yet he wanted to talk

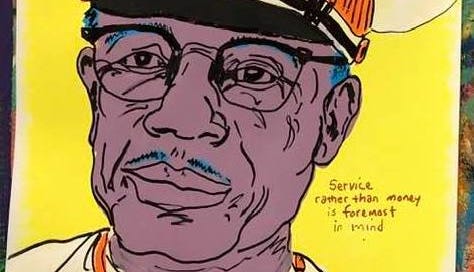

Gil Askey sketch by Tim Kerr

more about musicians he played with at Anderson. Askey did not go easily from memories of Rip Ross to Diana Ross. “I’m gettin’ to that,” he’d say whenever a question about his career was posed, “but first I’m going to tell you the stuff people need to know about.”

Askey’s mother was Ada DeBlanc Simond, the noted African American historian and author who penned the “Looking Back” column in the American-Statesman for several years. Askey’s father Aubrey left when Askey was 2 and, with his mother already having three kids by age 26, he was raised by his grandparents Gilbert and Mathilde DeBlanc, Creoles from Louisiana, who spoke French in the house.

Askey’s cousin was R&B singer Damita Jo (DeBlanc), who had minor hits with answer songs “I’ll Save the Last Dance for You” (1960) and “I’ll Be There,” to the tune of “Stand By Me,” the next year.

Joyce had recruited a 10-year-old Askey in 1935 to start playing trumpet at Kealing Middle School, whose band he also ran. “I was shooting marbles, and this kid said, ‘You should try out for the band,’ and I said, ‘the band’s for sissies. I want to play football,’ ” Askey recalled. Joyce overheard that exchange and within days Askey’s grandmother was in Joyce’s office. “He sold her an old beat-up Martin trumpet for, like, $10, and the next thing you know I’m taking lessons from Mr. Joyce.”

Like most of the neighborhood kids, Askey was intimidated by Joyce, who would carry a small billy club at band practice and rap kids across the back if they were goofing off. “I came to realize he had another side to him,” said Askey. “He really cared about us.”

The interview at Denny’s was connection weak, as Askey looked at me over his thick glasses like I didn’t have a clue about any of this. I had been waiting years to interview Askey, but by the time Luther Simond came to pick up his 85-year-old stepson I didn’t have much of a story. I gave Askey my home number if he wanted to talk some more and to my surprise, he called the night before he was to fly back to Australia, and we had a great talk for about an hour. If he was making a musical point, like how he’d jazz up “Reveille” in the Army, he’d play his trumpet into the receiver.

What set Askey apart from all the other horn players of East Austin was a gift for arrangement and composition that he didn’t know he had until enrolling at the prestigious Harnett National Music Studios in Manhattan after getting out of the Army Air Corps in 1944.

As an almost required rite of passage for Texas jazz musicians, Askey played for the Houston-based Milton Larkin Orchestra for a year before Hartnett. “You could say that was the time when the trumpet took over my life,” he said.

Askey started writing charts for full bands, eventually leading to his big break, a three-year stint as arranger/trumpet player with the popular Buddy Johnson band (“Since I Fell for You”). When rock ‘n’ roll exploded, Askey led the house band on package shows, backing Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, the Platters, the Clovers, Jackie Wilson, Lloyd Price and many more. “Bill Haley and the Comets were the only act on those tours that had their own band,” Askey said.

Askey received his first call from Motown on New Year’s Day 1965 with an offer to produce and arrange six tracks on Billy Eckstine’s Prime of My Life. He ended up doing the entire album.

To broaden the Supremes’ appeal in 1967, Motown mastermind Berry Gordy tapped Askey to produce The Supremes Do Rodgers & Hart. He also appointed him the group’s musical director on live shows, including the 1970 “Farewell” performance in Las Vegas that was Ross’ last show before going solo. Gordy called Askey “the glue that kept it all together.”

During his Austin visits, Askey stayed with Luther Simond at the house on Hamilton Avenue where his mother once cooked chitlins for the Supremes and the Manhattans on an off day on tour. “One of the girls said, ‘This is good; what is this?,’ ” Askey said, with a laugh. “I didn’t have the heart to tell them that they were eating hog guts.”

While touring Australia in 1973, Askey and a few other band members were caught in the rain and couldn’t find a cab. A woman pulled up and gave them a ride to the hotel. Seven years later, Askey married the good Samaritan, named Hellen, and relocated to Australia, where he became a new father at age 55.

In ’82, Askey flew to Los Angeles for what looked to be a month of work, helping to put together the spectacular Motown 25 program, which featured a Supremes reunion, plus Michael Jackson’s sensational first moonwalk to “Billie Jean.” Askey’s main role was arranging and conducting a soul throwdown between the Four Tops and the Temptations, but his month in the States turned into more than a year when a tour was thrown together after the success of “M25.”

His wife wasn’t happy about that, especially having to raise an infant alone, so Askey retired from touring in 1985. He was well-known in Australia through his work with programs that encourage young people to learn instruments. The former altar boy at Holy Cross Catholic Church in East Austin went to mass every Sunday until he passed away in 2014 at age 89.

He said he regretted that he was unable to get off work as music director of the movie Fame to attend B.L. Joyce’s funeral in 1980. But he sent a poem, an “Ode to B.L. Joyce,” which he wrote about the tailor who became one of Austin’s greatest teachers.

“I could’ve been Gil Askey the carpenter… Or Gil Askey the doctor. But I became Gil Askey the musician,” said the poem, which was read at the funeral. “B.L. Joyce lives in the things which I do, for without him there’d be no me,” it read. “Therefore, I’m an extension of him.”

Read more on Kenny Dorham, Damita Jo and Gene Ramey.

RELATED: I.M. Terrell High in Fort Worth was a wellspring of jazz greats.

I got turned onto the story of the L.C. Anderson band when I was researching the shooting death of Blaze Foley. The man who killed him was Carey January, a former student at Anderson High, so I got ahold of the alumni association. A Mr. Reid told me January had attended the latest reunion and showed around some plaques and citations from the California governor's office for his work getting health coverage for the poor in South Central. "If you want to do a real story about Anderson, you should write something about B.L. Joyce and the Yellow Jacket Band," he said, and got me in touch with Alvin Patterson, who replaced Joyce as band director in 1954. This is an old story I rewrote for "Ghost Notes."

Fantastic article.